|

|

March 4, 1998

Journal: In Quebec, the Remaining Quintuplets Are Broke and Bitter

By ANTHONY DePALMA

T. BRUNO, Quebec -- They are no longer as hard to tell apart as when they were children, dressed in different colors and forced to wear name tags so tourists at Quintland could identify them. Cecile Dionne's face is now a bit fuller than her sisters'; Annette's is somewhat sharper and Yvonne's more drawn.

But all three surviving Dionne quintuplets -- once among the best-known and most photographed children in the world -- share the same sad eyes, pinched by memories they wish they did not have.

The three women, now 63 and living together in a modest house in this Montreal suburb on the equivalent of $525 a month in pensions, have emerged from decades of seclusion and spent the last few months digging through their past in painfully public ways.

They are asking the current government of the province of Ontario, where they were born on May 28, 1934, to poor French-Catholic parents they never really knew, to give them a full accounting of their early years, when they were a bigger tourist attraction than Niagara Falls.

They want to know what happened to around $1 million that disappeared from a trust fund set up for them when they were taken from their parents' farm home in Corbeil, Ontario, and made wards of the state.

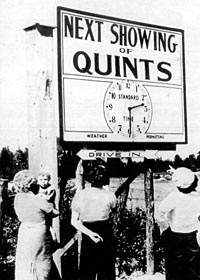

They want a public inquiry into the millions of dollars their fame brought to Ontario during the Great Depression when 3 million tourists visited the rural compound where the world's first surviving quintuplets were put on display three times a day.

In short, Yvonne said, "we want to find the real truth."

While the Ontario government has so far rejected any legal responsibility for the plight of the three sisters, it has accepted a moral obligation to help. Last week Premier Mike Harris offered them, but not the survivors of a dead sister, a take-it-or-leave-it offer of $1,400 a month apiece for life, if they agreed to drop all claims to future compensation.

"There are lots of people who would like money and lots of investments that have gone wrong," Harris said. "We decided instead of playing hardball to give a compassionate, caring response."

The three extremely shy women went before the cameras they so dislike to denounce the offer as little more than an attempt to silence them. "We want justice," Cecile told reporters at a news conference last week, "not charity."

The three Hollywood movies made about the lives of the Dionnes had much happier endings. They were five of the world's first global celebrities and were used to market everything from toothpaste to war bonds (although they were never told that a war was actually going on).

Ironically, the provincial government took them from their parents when they were a few months old to prevent their exploitation. Their desperate father, Oliva, had signed a contract with some American promoters to display the babies at the World's Fair then being held in Chicago. The father canceled the contract a day after he signed it, but it was already too late.

The sisters can only guess how different their lives might have been had the government not stepped in. They cannot even be sure they would have lived at all. Their farmhouse was 12 miles from the nearest hospital, and no quintuplets had ever survived without intense medical care.

"There are still questions I am wondering about," Cecile said after a long, uneasy pause. "If we had stayed with them, could we have been able to survive?"

The government built the Quintland compound across the road from the family homestead. There the five button-nosed girls led what was widely seen as a privileged life, as miraculous in the somber days of the Depression as was their very survival. They had round-the-clock nursing care, they played on miniature pianos and they even had their own playground and tiny swimming pool.

But it was not the paradise shown on newsreels.

"When we were displayed, there was a playground," Cecile said in halting English. Although the playground was surrounded by special glass that allowed the tourists to see in without being clearly seen, the girls saw their shadows and always knew they were being watched.

"We were hearing the noise," Cecile said. "We knew they were there."

The quintuplets were allowed to leave the compound only a handful of times. Their parents were allowed to visit, but to the girls they were simply two more visitors who had to wear surgical masks to keep from spreading germs. "We didn't know each other," Cecile said.

Eventually the parents won back the girls. They were almost 10 years old by then, and a large house was built with the proceeds of their promotions and endorsements. Eventually one of the rooms became a classroom for the sisters and 10 carefully selected classmates. For the first time, they realized that other people did not live the way they did.

"I remember being very surprised to see girls like us who seemed to be very happy with their families," Cecile said. "It was not like that for us."

About $1.8 million was put into a special trust fund for the quintuplets' future. By the time they turned 21, less than half remained. It was divided among four of the girls; the fifth, Emilie, had entered a convent but died at 20 after an epileptic seizure.

The other sister, Marie, died in 1970 from a blood clot in the brain.

The girls had been raised to believe they would be taken care of by the trust fund. When forced to handle money, they were totally unprepared. Cecile said they had trouble distinguishing a nickel from a quarter.

"We tried our best," Yvonne said. And they agree that they made mistakes.

Cecile says she married the first man who took her for a cup of coffee. She had five children in five years and then left him. Annette and Marie also married and raised families, and their marriages also failed.

By the time they turned 60, they were under such emotional and financial stress that they wrote a book with a professional author. Revelations of sexual abuse by their father briefly increased sales. But the advance of about $37,000 did not last long.

Last year, Cecile's son Bertrand forced the government to open records from the 1930s and '40s that revealed many instances of how money that was supposed to have been put aside for the quintuplets went instead to Quintland, where it was used to pay for things like toilet paper for tourist bathrooms.

After all these years, they are living together again. In 1992, Cecile, who had studied nursing, could no longer afford her Montreal apartment and so moved in with Annette, who owns the house in St. Bruno. Yvonne, who like Annette, had become a librarian, underwent surgery in 1993 and afterward went to live with her sisters.

Annette's son pays the mortgage, and the three women pool their $525 in pensions to barely cover their bills.

More than anything, they feel betrayed. Last year, when Bobbi McCaughey gave birth to the world's first surviving septuplets in Iowa, the sisters sent them an open letter that was published in Time magazine.

"We hope your children receive more respect than we did," they wrote. "Multiple births should not be confused with entertainment, nor should they be an opportunity to sell products."

Annette, who like all her sisters suffers from epilepsy, is feeling poorly these days. She came out of her sickroom just long enough to say that what is most painful about reopening the past is realizing how thoroughly she and her sisters had been deprived of their private lives.

"It is hard to see that everything you have is exposed all over the world," she said. Cecile believes that by refusing to recognize their individual identities, the government had "stolen our souls."

Yvonne, sitting quietly on the end of a worn-out sofa, timidly added, "And they are still doing it."

|