I had twice been to Nuristan, in North East Afghanistan, in 1977 and 1978. I had both times been to Bargematal, which is the last village on the only road in Nuristan. In May, 1978, I drove my red Volkeswagon Beetle to Nuristan. This was a fantastic accomplishment. I became the first person ever to drive a car to Nuristan. Jeeps and vans had been there before, but not cars.

|

I later found out that this incident had made me famous in Nuristan. I later drove the same car to Chitral, in NorthWest Pakistan. By then, most of the Nuristanis were refugees in Chitral. Some of them told me that they did not remember me, but they did remember my car, the first car ever to make it to Nuristan.

I had purchased the car in Munich, Germany in February, 1978. I drove it from Germany to Austria, Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria, Turkey and Iran, finally reaching Afghanistan.

I only spent one night in Nuristan. I was detained by the police and it seemed that they were going to arrest me. I was sitting in the new Governor's office. This was in a village on the main road, but directly below Kamdesh. A bunch of Nuristani were in the Governor's office. The Governor was issuing the orders of the new Government of Nur Mohammad Tureki, which had just taken power in a coup two weeks before. I could see that the Nuristanis did not like what they were hearing. It seemed that the new governor was trying to turn Nuristan into a Marxist Worker's Paradise. I was thinking that they were going to kill this guy.

Later on, I asked what had happened to that man. The Nuristanis told me that he had run away in the night. Apparently, he realized the same thing that I had realized, that otherwise they were going to kill him.

I decided to get out while the getting was still good. I was relieved when my car finally made it down to Jalalabad. However, that was not the end of my story, but only the beginning. Although I had made it safely out of Nuristan, I was still in Afghanistan. Two weeks later, I was arrested in Village Khaway, which is North of Navzad in the Helmand Province of Afghanistan. I have described the next phase of my story in an article I wrote entitled "How I Escaped from Jail in Afghanistan".

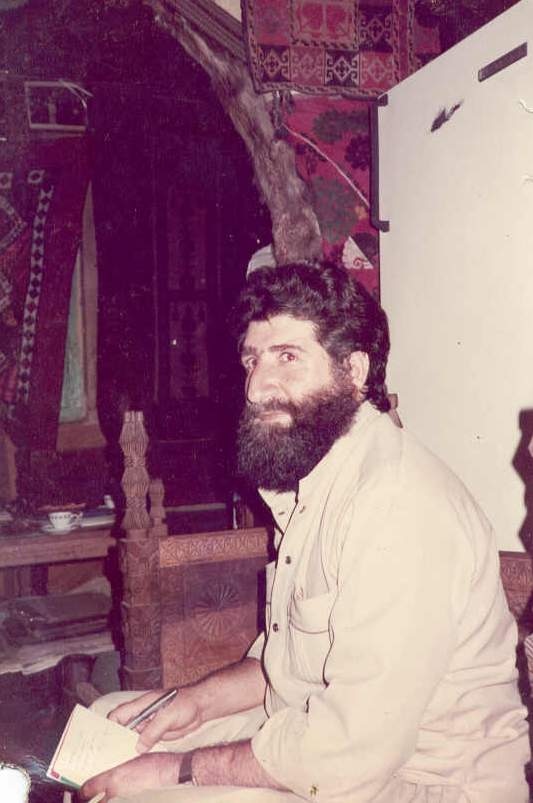

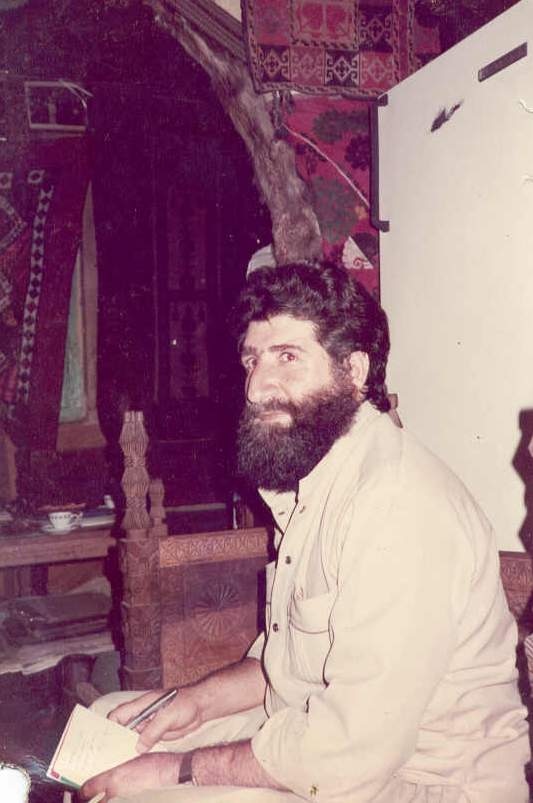

Thus, when safely back in America in 1979 near the campus of Columbia University, I was surprised to find that somebody from Nuristan had made it to America. As it turned out, Khalilullah Nuristani was not just any Nuristani. His father had been one of the most important people in Nuristan and was regarded as their leader. This probably explained how Khalilullah had been able to get a visa to America.

As I was going back to Chitral, Khalilullah asked me to carry a camera to another Nuristani named Shah Wali. The purpose of the camera was to take pictures of Nuristan which Khalilullah would have published in America. Khalilullah purchased the camera in a shop and gave it to me. I took it to Chitral, Pakistan, where I found Shah Wali in a refugee camp. I gave him the camera.

As I was leaving for Pakistan, Khalilullah had asked me to find out news about his family, his wife and his children. I asked Shah Wali. Shah Wali told me that two of Khalilullah's children had been killed, but he told me not to tell Khalilullah. Shah Wali explained that they had not written this news to Khalilullal, because they were afraid that he might be upset about this.

I wrote down the names of the two children who had died. When I returned to America, I told Khalilullah, anyway. I knew that if something like that had happened to my children, I would want to know and I would be upset if nobody had told me.

Some time later, when I went up to Columbia University to see Khalilullah, I found out that he had left and gone back to Afghanistan. Those who knew him had been surprised. They said that he had just abruptly left. Although he had a green card application pending and had been just on the verge of receiving it, he had suddenly without warning had left America and had gone back to Afghanistan.

In 1983, again I went to Chitral, Pakistan. There, I found Khalilullah living in a house directly in front of the Royal Palace of Chitral (known as the "Noghor" in the Chitrali language). Khalilullah was styled as the "Foreign Minister of Nuristan". The fact that he was completely fluent in six languages, including Farsi, Pashtu, Urdu, English, Khowar and Nuristani, was helpful. What this meant in practical terms was that he was the Chief Consular Officer for Nuristan. Groups of Nuristanis would come to him for a pass or essentially a visa to enter Nuristan. Without his permission, they could not enter Nuristan. There were several high mountain passes connecting Chitral to Nuristan. The lowest pass was 14,000 feet high. In spite of dropping bombs and land mines, the Soviets had never been able to close those passes. They had even dropped bombs disguised as children's toys, which would blow up and kill the child who tried to play with it. The Nuristanis had boarder guards at the top of the passes and, without a pass signed by Khalilullah, nobody could enter Nuristan.

|

Prince Mohay-ud-Din, the District Council Chairman of Chitral and later the Minister of State of Pakistan, was also directly concerned with Khalilullah Nuristani.

Since 1983, I have not been involved with Khalilullah until a few months ago when his family did an Internet search and found that I had mentioned his name on my website at http://www.shamema.com/macedon.htm .

In a war-torn nation like Afghanistan, where survival alone is problematic, Khalilullah has managed to survive, although just barely. He is now seriously ill with diabetes. He was not expected to survive but still he is alive. He was also kidnapped and he and his family have been assaulted many times. His connection with America and Canada have made him a target for groups associated with the Taliban.

Amazingly, two of his daughters have made it to Canada and are top students there. His second daughter is named Zainab, but her friends call her "Zeena, the Warrior Princess". Zeena has graduated as the valedictorian of her class two times.

Considering their background, it is truly amazing that two Nuristani girls have made it to Canada. Nuristan has long been a land the subject of myths. The story which has long been told is that when the soldiers of Alexander the Great crossed the Hindu Kush in 327 BC, they encountered the Nuristanis. Five of Alexander's soldiers stayed behind, intermarried, and modern day Nuristanis are descended from them. The story of a light-skinned European race descended from Alexander the Great and living high in the Hindu Kush Mountains whom nobody had ever actually seen was dismissed as a myth by the early Europeans to reach India. Believing that it was a fable, Rudyard Kipling wrote a story about them entitled "The Man Who Would Be King", which in 1975 was made into a feature movie starring Sean Connery. Nobody believed that these people actually existed until the British Explorer and Military officer George Robinson went there in 1892. Robinson wrote a book about them entitled "Kafeers of the Hindoo Kush" which is available in most libraries. Shortly thereafter, the British signed a treaty which divided the territory between Afghanistan and India. The Durand Line was drawn by a British military officer named Mortimer Durand. The Mitar of Chitral asked to be included in India, so the Durand line was drawn so that Chitral was in the part of India which is now Pakistan. Although Nuristan, which was then known as Kafirstan, was to some extent part of Chitral, it was left in Afghanistan when the Durand Line was drawn. This induced King Abdul Rehman of Afghanistan in 1893 to attack Nuristan and incorporate it into Afghanistan. King Abdul Rehman also forced the people of Kafirstan to give up their Kafir religion and convert to Islam. King Abdul Rehman renamed Kafirstan as Nuristan, which means "The Land of Light".

The British Press was outraged when King Abdul Rehman did this. When asked why he had done this, King Abdul Rehman wrote that the Nuristanis were such savages that, whenever they came to Kabul, they were dressed in animal skins and they sold their wives as slaves.

The Nuristanis have never been happy about what King Abdul Rehman wrote about them. However, they confirmed their reputation as fierce mountain tribesmen in 1978 when they were the first group to rise up in armed rebellion against the new Communist Government of Afghanistan. Everybody agrees that the War in Afghanistan started in Nuristan. This was very shortly after I was last in Nuristan in May, 1978. (Did I start the war, as some say?)

Ismail Sloan