Files reveal how FBI hounded chess king By Peter Nicholas and Clea Benson Inquirer Staff Writers

He was the ultimate cold warrior, humbling the mighty Soviet chess establishment through his own genius and a pounding ambition to be the greatest player in the world.

At a time when competition with the Soviets was measured in moon landings and missile counts, Bobby Fischer beat the Russians' best.

|

FBI records obtained by The Inquirer under the Freedom of Information Act show that intermittently, from the 1940s to the 1970s, the Fischers were being watched.

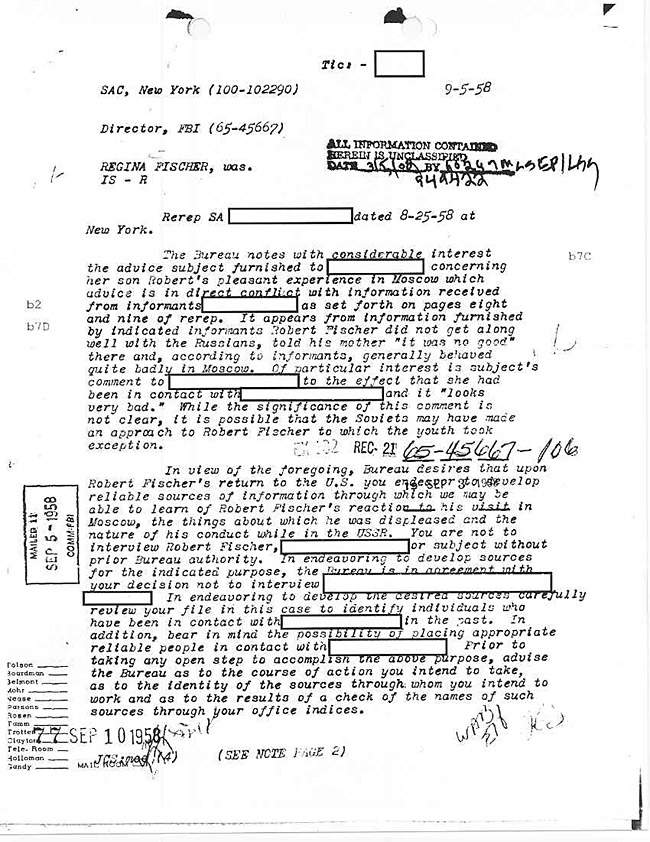

The FBI worried that the Russians had tried to recruit the young chess prodigy on a trip he made to Moscow in 1958.

FBI agents checked birth records, posed as student journalists, and considered cultivating other chess players. They hounded Fischer's mother, reading her mail, quizzing her neighbors, studying her canceled checks.

They eventually decided Regina Fischer was no spy, and that the Soviets hadn't tried to enlist her son.

But the FBI files offer insights into another era, and into long-buried secrets about who Bobby Fischer is and who his parents were.

His father has widely been identified as a German biophysicist named Hans-Gerhardt Fischer. But documents suggest it was someone else entirely.

The FBI kept a file on that man, too.

The files are a glimpse into the world of J. Edgar Hoover's FBI, where agents in the Cold War pursued citizens of leftist leanings with a fevered intensity and few restraints.

Now 59, Bobby Fischer has become a reclusive, anti-Semitic expatriate. Efforts to interview him for this article were unsuccessful.

He has been seen in Japan, Hungary and the Philippines. In a Philippine radio interview on Sept. 11, 2001, he applauded the terrorists' attacks and said America should be "wiped out."

Chess experts have analyzed Fischer's games in astonishing depth. Even the offhand games he played blindfolded have been exhumed and published like lost works of literature.

But his life is largely a mystery. Bruce Pandolfini, a noted chess teacher who was featured in the movie Searching for Bobby Fischer, said of Fischer's beginnings: "Nothing is known."

Regina Fischer's 750-page FBI file is publicly available because she is deceased. A pediatrician, she died of cancer in 1997.

The file touches only a sliver of her son's chess career - a trip he took to Moscow in 1958, when he was already the champion of U.S. chess at age 15. But it offers sweeping detail about the Fischer family's origins, friends and associates.

It was quite a circle.

Regina Fischer's German husband, Hans-Gerhardt Fischer, had fought the Fascists in the Spanish civil war in the 1930s. Her close Hungarian friend, Paul Nemenyi, specialized in fluid mechanics - a science applied to everything from blood flow to jet design. The FBI claimed that both men harbored Soviet sympathies.

Regina Fischer spoke eight languages. She was brilliant but paranoid, a psychiatrist determined in 1943.

Then again, she really was being followed.

The FBI went so far as to read case notes compiled by the social workers Regina Fischer visited as a struggling single mother who moved from state to state. During her pregnancy, she considered putting her baby up for adoption.

Did she hear FBI footsteps? "Absolutely," said her son-in-law Russell Targ, now a physicist in Palo Alto, Calif. "They made it hard for her to keep a job."

She raised Bobby in Brooklyn. They were poor; in a 1952 letter, she said she couldn't afford to patch his torn shoes.

The FBI began watching her and her circle in the 1940s. The last entry in her file is in 1973: Agents noted her opposition to the Vietnam War.

Some of the orders in the file came straight from Director Hoover's office. For his FBI, she was a tempting target.

In the 1930s, in her teens, she moved from the United States to Germany and then Russia, where she lived from 1933 to 1938 and attended medical school.

Agents described her as "a person who would be ideologically motivated to be of assistance to the Russians."

In 1942, someone went through her papers, found politically tinged letters, and telephoned the FBI. That is what drew the agency's attention.

The FBI learned in 1957 that Regina had contacted the Soviet embassy to discuss the trip her son would take the following year for matches in the Soviet Union.

Alarms went off.

Before Bobby Fischer left for Russia in the summer of 1958, an agent posed as a college journalist to interview producers of the TV show I've Got a Secret. Bobby had been a guest on the show and won plane tickets to Russia. (Fischer's "secret?" He was U.S. chess champion. The panel was stumped.)

Despite playing well in Moscow, Fischer was peeved at not being matched with the Soviets' best.

The FBI heard from another informant: Fischer had called his mother in the United States and told her, "It's no good here."

Agents weren't sure what to make of that. So they guessed.

"[I]t is possible that the Soviets may have made an approach to Robert Fischer to which the youth took exception," Hoover's office wrote to the New York field office in September 1958.

The next month, New York agents reported their finding: Fischer was a moody adolescent who didn't get along with his mother.

Agents made it their business to find out who Fischer's father was. They checked his birth certificate; it listed his father as Gerhardt Fischer. He and Regina Wender had married in Moscow in 1933.

They divorced in 1945, two years after Bobby's birth, but the FBI believed they had been apart longer than that. Regina Fischer came here in 1939; the FBI said her husband never entered the United States.

The FBI file says Gerhardt Fischer lived for a time in Chile, where he sold fluorescent lights and worked as a photographer.

The FBI suspected he might have been a Soviet spy there in World War II, targeting Nazis. The evidence? In a letter to Regina Fischer, he had made what the FBI called a "cryptic" reference to photographing fishermen at a Chilean port.

The file noted that several German agents had been arrested there, posing as fishermen.

The FBI seemed to pay more attention to Regina Fischer's Hungarian friend, Paul Nemenyi.

Nemenyi came to the United States in the 1930s, taught college mathematics, and met Regina Fischer in 1942, according to the files. An informant told the bureau that in 1947, Nemenyi opined that the Soviet system was "superior to that of the U.S."

Nemenyi also took a deep interest in Bobby Fischer. He paid child support and complained to social workers about the way Regina was raising the boy.

A social worker told the FBI of interviewing Nemenyi in 1948. This informant dutifully reported that as they spoke about Regina, Nemenyi had wept.

The heavily censored files don't say whether Nemenyi was Fischer's father. Letters obtained by The Inquirer offer an answer. They are the papers of Nemenyi's late son Peter, a civil-rights activist who gave them to a state archive in Wisconsin.

"I take it you know that Paul was Bobby Fischer's father," Peter Nemenyi wrote after his father's death in 1952. The papers also include a plaintive letter that same year from Regina Fischer to Peter Nemenyi.

"Bobby... was sick 2 days with fever and sore throat and of course a doctor or medicine was out of the question," she wrote. "I don't think Paul would have wanted to leave Bobby this way and would ask you most urgently to let me know if Paul left anything for Bobby."

In the end, that's the picture the FBI was left with: nothing more than a worried single mother with a troubled son.

A son whose mind could come up with the most sophisticated chess moves - and the most extreme ravings.

After beating Boris Spassky for the world title in 1972, Fischer dropped out of competition.

He resurfaced in 1992 to beat Spassky again, in Yugoslavia. That got Fischer indicted: The Justice Department alleged he had violated U.N. sanctions imposed on Yugoslavia. If Fischer reenters the United States, prosecutors say, he faces arrest.

In the radio interview last year, Fischer said: "No one has single-handedly done more for the U.S. image than me... . When I won the world championship in '72, the U.S. had an image of a football country, a baseball country. No one thought of it as an intellectual country."

He described Jews as "thieving, lying bastards. They made up the Holocaust."

The irony is clear: His mother was Jewish and so was Nemenyi, the man described by some as his father.

There is another irony: Fischer is wanted by the same Justice Department whose agents once tailed his mother - even though they came up empty-handed.

"A review of this case fails to reflect that the subject has been involved in Soviet espionage, and actually, there has been no allegation that she has been so engaged," reads a 1959 report.

Contact Peter Nicholas at 202-383-6046 or pnicholas@krwashington.com

Here are links: